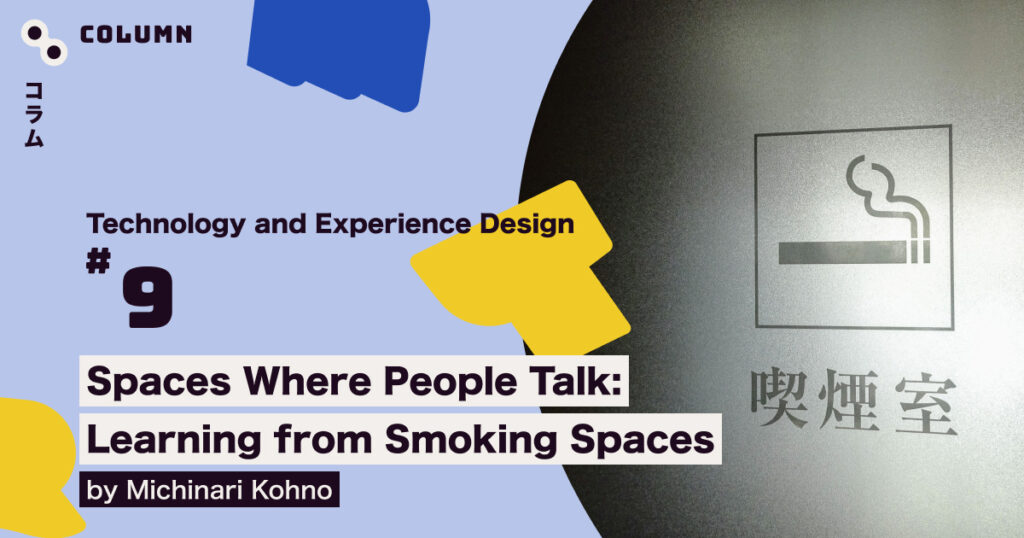

Living as Your Best Self in REALITY’s Anime Avatar Experience

“REALITY,” an app that lets users enjoy live streaming through avatars, has become popular not only in Japan but also overseas. As this new form of entertainment and communication becomes more mainstream, what are the key values the team behind REALITY emphasizes? We sat down with designers Kazunori Yamamoto and Akihiko Iwasa, who are responsible for global expansion, to find out more.

Kazunori Yamamoto | Product Design Team Manager, Platform Division, Product Department, REALITY Inc.

After working at a tourism startup, Kazunori joined REALITY as its first UI designer. His hobby is cooking, and lately, he’s been into creating dishes using Japanese sansho pepper.

Akihiko Iwasa | Head of Global Strategy, Platform Division, REALITY Inc.

With a background in consulting and a stint at DeNA Co., Akihiko joined REALITY in 2023. After managing the domestic live-streaming business, he now oversees the global business.

REALITY: “Live as your best self” with avatars

— To start, could you tell us about REALITY?

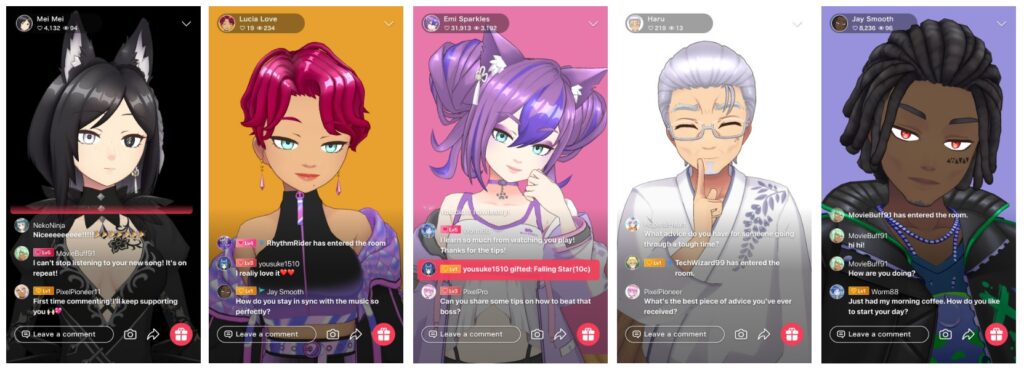

Kazunori: REALITY is an app where anyone can use just their smartphone to become an avatar and enjoy live streaming, game streaming, chatting, and virtual communication.

Kazunori: Our vision is “Live as your best self.” We believe that if people were freed from the physical limitations of their bodies, they could express themselves more freely, enjoy communication in new ways, and discover new possibilities for themselves. This idea is what led us to focus on live streaming through avatars.

The term VTuber is pretty common now, but from the start, we’ve been consistently working toward a world where anyone can easily use avatars in their everyday lives.

— You emphasize lowering the barrier for beginners to start streaming. What kind of features make that possible?

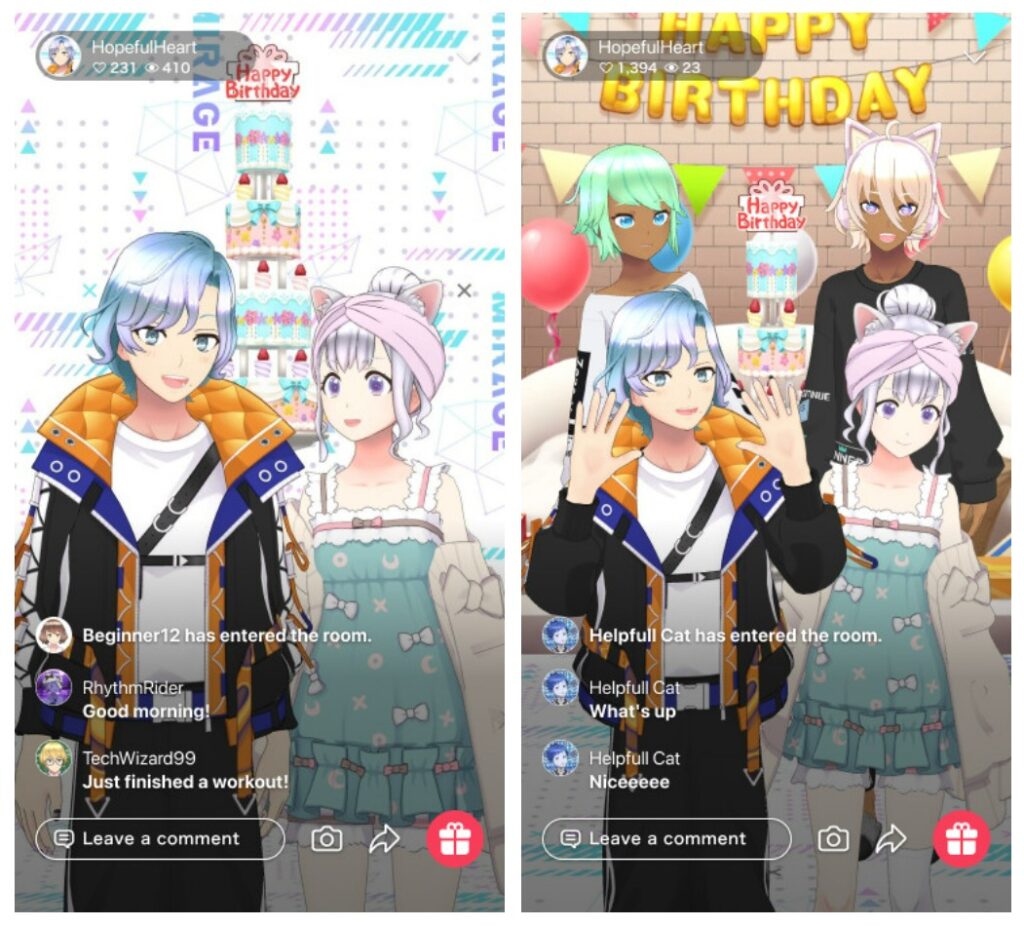

Kazunori: We’ve included many features that make it easy for users to join streams without realizing it. One example is the collaborative streaming feature, which allows you to join someone else’s stream as a guest. As a guest, you can interact with viewers, so even if you’re not planning to stream yourself, you can still experience what it’s like—maybe reacting to comments and seeing how much everyone enjoys it.

Akihiko: In most live-streaming apps, the roles of streamer and viewer are separated. Streamers visiting someone else’s stream can sometimes feel like they’re doing a bit of self-promotion rather than just enjoying the content.

On the other hand, in REALITY, the line between streamers and viewers is very blurred, which is a key feature of the app.

So, unlike the typical image people have of VTubers as being like celebrities, most of our users don’t think of themselves as particularly special. Many of them just find themselves streaming naturally after chatting with friends they’ve made on REALITY. This is one of the unique user experiences that makes REALITY stand out.

Expanding use cases to embrace different forms of enjoyment

— What are some distinctive elements of your approach to service development at REALITY?

Akihiko: Instead of focusing on one use case, like live streaming, and continuously adding more sophisticated features, we aim to expand sideways by adding features for different use cases. This broadens the ways people can enjoy the app.

For example, aside from the usual booth streaming feature, we also have room streaming, where users can design a space and enjoy it like a miniature world viewed from above. Some users spend time redecorating their rooms or coordinating outfits just for fun. Naturally, this means the number of booth streams might decrease, but we see this as another use case.

Akihiko: In 2022, we added a feature that allows users to make video calls to friends from the chat. This isn’t live streaming anymore, but the appeal of blurring the lines between streamers and viewers, like in a social network, has resonated well with users.

— What impact does offering such a wide variety of features have on your service?

Akihiko: By introducing a range of features, we create multiple entry points for users to join the app. As they explore these different ways of using REALITY, they discover new possibilities, which attract an even wider audience. It creates a positive cycle.

Kazunori: Of course, some users view REALITY as a place for live streaming to make money or gain recognition from others. We’ve also developed features for these users, and that’s one valid way to use the app.

However, at the core of our service is providing a space for communication and self-expression through avatars, so we’ve built many features that go beyond live streaming alone. This is what allows us to create the kind of relationships where the boundaries between streamers and viewers blur, as they do now.

— That said, I imagine you still need a consistent framework or guiding principle for the service. How do you manage that?

Akihiko: That’s definitely something we wrestle with. REALITY can be a social platform, a live streaming app, and also a service for dressing up avatars or designing rooms. It’s tough to maintain balance without one aspect overshadowing the others.

For example, even with something like “changing your avatar’s outfit or redecorating your room,” we need to decide whether users should only be able to do it during a stream or also when they’re not streaming. That creates a bit of conflict between the live-streaming focus and the avatar customization side of things. These are the kinds of issues we’re constantly reviewing and fine-tuning.

— When prioritizing features, how do you consider the diversity of users and use cases?

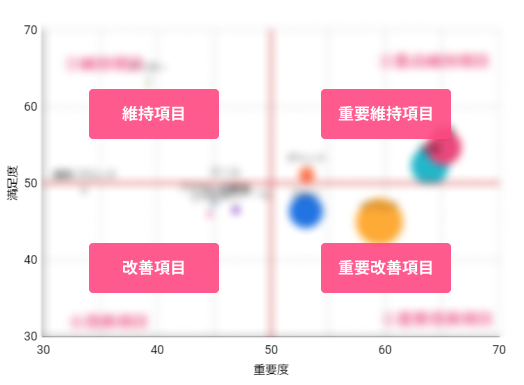

Akihiko: Since the use cases are so varied, the users are equally diverse. If we only release features that seem irrelevant to a particular group, their satisfaction could decrease. That’s why balance is so important. We regularly plot out user satisfaction and dissatisfaction to ensure no single aspect is being over- or under-served. This helps us keep track of the overall balance and adjust accordingly.

Akihiko: We plot user feedback based on the importance of their opinions and the strength of their requests. For example, this lets us see how implementing a feature related to avatars reduces the number of requests in that area. By using this visualization and constantly balancing our actions, we aim to minimize the gap between what users are asking for and what they’re satisfied with.

The different ways Japan and overseas users enjoy the app

— You’ve seen a rise in overseas users. How do they differ from those in Japan?

Kazunori: In terms of live streaming, there’s a much higher ratio of collaborative streams (where users stream with others) among overseas users compared to Japan. There’s also a significantly higher usage of video calls.

Akihiko: Take the U.S. market, for example. The foundational experience for live streaming there often comes from Twitch (a live-streaming platform by Twitch Interactive). In contrast, for Japan, it’s likely rooted in platforms like Nico Nico Douga. These foundational experiences play a major role in shaping user expectations.

On Twitch, game streams, often featuring competitive gameplay, are highly interactive, where the streamer reacts to the game, and viewers enjoy both the game and the streamer’s reactions. There’s a dual-layer of interaction: the streamer’s reaction to the game and the audience’s engagement with the streamer. If there’s no content to react to, like a game, streams tend to fizzle out. This is why collaborative streams and video calls are more common in markets like the U.S.

On the other hand, Nico Nico Douga has a different dynamic. Viewers often leave comments to support or tease the creator, focusing more on interacting with other viewers than just the streamer. This results in a form of communication that thrives on real-time interaction between people, which fuels the streaming experience. I believe these early experiences have led to different expectations and use cases.

— The idea that expectations for streaming stem from foundational experiences is fascinating. How did you discover this difference?

Akihiko: We have team members who’ve lived in the U.S. and Canada for a long time, and through conversations with them, we’ve uncovered many insights. Also, during user interviews in these regions, we’ve often heard things like, “Here’s what feels off about REALITY.” Those moments of feedback reveal gaps in expectations, and through further investigation, we identified key points, like the differences in foundational experiences.

That said, just because there’s a difference, we don’t want to dismiss certain behaviors by saying, “That’s not how it’s meant to be used.” We’re open to a variety of ways users enjoy the app. Rather than pushing a “Japanese way” just because the service originated here, we want to create experiences that transcend our own preconceived notions.

Aiming for more inclusive best selves

— At the end of May 2024, you rolled out the major “REALITY Avatar 2.0” update, allowing for more diverse expressions of ethnic and cultural identities. What was the motivation behind this?

Kazunori: Currently, about 80% of our users are from overseas. Over time, we’ve received increasing feedback like, “I want my avatar to look more like me,” or “There’s a huge gap between how I look in REALITY and how I look in real life.” We also wanted to better meet the needs of users from various countries and regions, which led to this update.

— Do reactions to avatars differ depending on the country?

Akihiko: It’s hard to generalize by country, but we do see some trends.

For instance, among users who identify as Black, there are many different backgrounds and skin tones. When we first launched, we only offered 10 skin colors, and we received feedback that it didn’t allow for enough accurate self-expression. We’ve since increased that number to 30, and we’re considering even more customization options, like free skin color selection, to help users express themselves fully.

Another aspect we’ve noticed is that many users, especially overseas, don’t necessarily want to represent themselves as human. Characters like demons, aliens, and animals—identities that go beyond humans—are incredibly popular, more so than we initially imagined.

— That’s an interesting difference.

Akihiko: I think this also ties back to foundational experiences. In Japan, most characters in the anime or manga kids are exposed to growing up are human. But in American children’s shows, you often see characters like the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles or The Simpsons—aliens, animals, or stylized, non-human figures. So, when people think of their best selves, it’s natural for them to draw inspiration from what they imagined and enjoyed as children.

— So, this update aims to fulfill those diverse visions of the best self.

Akihiko: Exactly. But these deeper needs rarely surface as obvious pain points, so it’s difficult to capture. People don’t usually think, “I haven’t been able to be my best self lately.” For users to become aware of these deeper needs, they need to spend a long time on the platform and engage with others through streaming.

For people to use the platform for an extended time, though, we first need to make sure the basic service experience is comfortable. While improving the fundamental user experience, we’re also working toward creating value that addresses these deeper needs in the long term. It’s a challenging endeavor, but one we take pride in.

Achieving success overseas by engaging with each market

— How do you feel about your progress in expanding overseas?

Akihiko: At first, we were concerned about the gap in market maturity, the value we were offering, and how it was received in Japan versus the U.S. There were moments when we wondered, “Is it really possible to carve out a spot in the American market?” Historically, few Japanese services have gained major traction in the U.S., which added to our worries. At that time, we were mostly focused on whether we could succeed by exporting the Japanese version as is.

What changed was when we started working closely with local staff, gathering user feedback one by one, and learning what resonates with users in each region. We realized that aspects not emphasized in Japan were highly valued abroad, which led to discoveries like the different foundational experiences we discussed earlier.

Global expansion from Japan isn’t just about exporting a product as is and hoping it works in every market. It’s about learning how to navigate each market’s specific landscape, gradually adding value in areas where we excel. I knew in theory that we’d need to tailor our approach to each market, but it wasn’t until we actively engaged and received direct feedback from users that I realized just how much we hadn’t been doing.

— Where do you see the service currently in terms of overseas growth?

Akihiko: We haven’t even reached the early adopter phase yet. While experiences from Japan’s early days can offer useful insights, it’s not as simple as replicating what worked here.

That doesn’t mean we’re randomly testing things though. We’re carefully thinking through what to test and in what order. Should we benchmark local apps to understand what’s key to market entry, or trust REALITY’s unique features and let user feedback guide us? We’re at a stage where we’re rethinking past successes in Japan and considering a range of strategic options.

— What’s your main focus moving forward?

Akihiko: The key is to return to REALITY’s core vision “Living as your best self” and think about what that means to overseas users in terms of play and experiences. How can we exceed those expectations? Ultimately, the only way forward is to listen to users and keep building what they want. While this can lead to conflicts between different user expectations, we’ll continue to carefully prioritize and choose the right actions moving forward.

Related Links

REALITY Inc.

Virtual Communication App「REALITY」