The mui Board: Blending Technology Into the Rhythm of Everyday Life

The mui Board, a digital device crafted from natural wood, was introduced in 2020. More than just a controller for IoT devices, it offers features like weather display, handwritten messaging, and voice communication. But how did this unique product come to life, and what kind of role does it aspire to play in our homes? We spoke with mui Lab to learn more about their design philosophy and how they bring it to life.

Nobuyasu Hirobe | Creative Director, mui Lab Inc.

Nobuyasu Hirobe is the co-founder and Creative Director of mui Lab. After working as an in-house designer in the CMF (Color, Material, Finish) design field, he came up with the idea for the mui Board, which uses natural wood to realize a comfortable lifestyle through information technology. He explores the intersection between people’s daily lives and information technology through the tactile qualities found in everyday surroundings.

Eri Nishihara | UI/UX Designer, Design Department, mui Lab Inc.

After earning her degree from the Department of Scenography, Display, and Fashion Design at Musashino Art University, Eri Nishihara began her career at an internet company, where she handled UI/UX design for web services including avatar communities and educational platforms. She later deepened her expertise in design research at a design firm. Over the course of seven years as a freelance designer, she worked on a variety of projects with a focus on UI/UX and design research. Drawn to the philosophy of Calm Technology, she eventually joined mui Lab to further explore technology that harmonizes with everyday life.

The “mui Board”: A Subtle Display of Home Life in Harmony with Its Surroundings

To begin, could you tell us about mui Lab and your product, the “mui Board”?

Nobuyasu: At mui Lab, our mission is to create a life and society enriched by the gentle harmony of people, nature, and technology. Inspired by Mark Weiser’s concept of Calm Technology and grounded in a distinctly Japanese sense of aesthetics, we’ve developed a design approach we call Calm Technology™ & Design, which shapes the way we craft user interfaces and experiences.

We aim to build technology that feels as natural and unobtrusive as a piece of furniture. The mui Board exemplifies this vision — a touch panel display made from natural wood that integrates seamlessly into the home. It allows users to access information and control IoT devices while supporting communication through handwritten and voice messages. From weather updates to family event reminders, and from lighting to air conditioning controls, the mui Board offers a quiet, intuitive way to interact with the digital elements of daily life.

Nobuyasu: Various household devices such as lighting and appliances are networked together, with their statuses visualized on the mui Board through simple pixel art. At first glance, this might seem redundant — you can see these devices around you when you’re at home. But this design is an intentional step toward the near future. Instead of focusing solely on control, our aim is to quietly surface the state of the home, making the invisible visible. By presenting this information gently and accessibly, we believe people can make more thoughtful, informed decisions about their environment.

When We’re Together, Our Attention Is on Our Screens — Is This a Healthy Way to Live?

The mui Board has such a calm, understated presence. Was there a particular frustration or discomfort with how technology is usually designed or used that inspired its creation?

Nobuyasu: This photo captures a moment from my own home in the past — everyone was absorbed in their smartphones. Even when I said, “Let’s eat together,” their eyes stayed glued to the screens. It’s exactly because these devices are so convenient that we can’t help but be pulled into them.

It seems that many households today are experiencing this kind of situation.

Nobuyasu: When family members are in the same space, it would be nice to enjoy everyday conversations — about the day’s plans, groceries, or just small talk. But when everyone is preoccupied with chatting to someone far away through their phones, drawn outward instead of inward, it creates a quiet kind of loneliness.

I also feel that the way we physically engage with devices — our posture, our focus — isn’t particularly healthy. It’s time to rethink our relationship with technology and move toward a more balanced, wholesome way of living. That reflection was one of the inspirations behind the mui Board. We’re exploring how technology can gently support family interactions — not by taking center stage, but by blending into daily life and enhancing it from the background.

What We Use in the Home Should Be Made of Materials Found in the Home

Another distinctive feature of the mui Board is its use of natural wood. Could you tell us more about that?

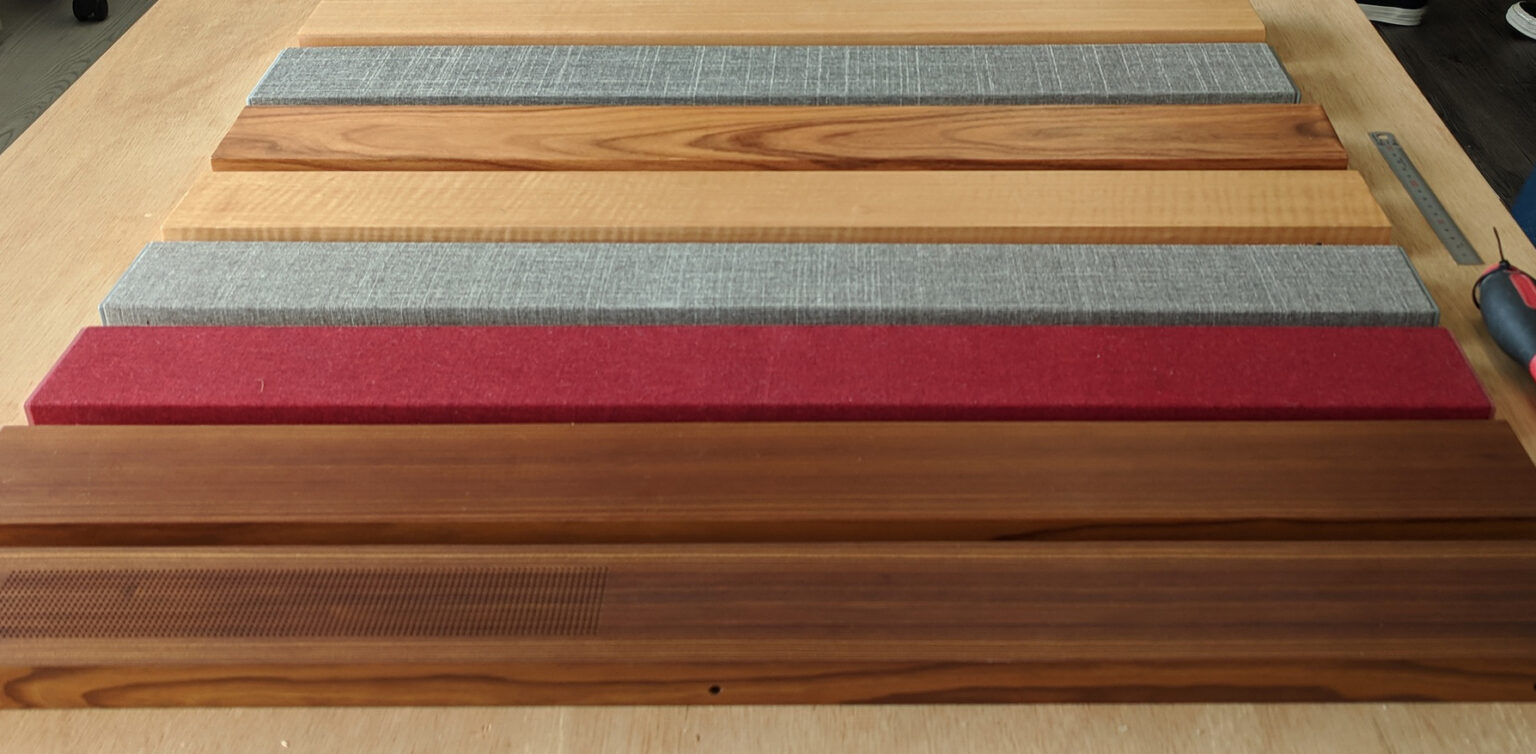

Nobuyasu: Unlike most smart home products that are operated via smartphones, the mui Board offers a distinctly different experience — one where you engage with information while physically sensing the natural texture of wood, thanks to carefully preset configurations.

Before choosing wood, we experimented with a wide range of materials. Since this product was intended for home use, we felt it should be made from materials that already feel at home — glass, metal, stone and fabric. We built prototypes using each, and when we had people try them out, the response was overwhelmingly clear: “Wood is the best.” Many were captivated by the unique charm and almost magical quality of wood.

As we deepened our exploration, our team traveled to Hida Takayama — a region renowned for its traditional woodworking. There, we spoke with local lumberjacks and even participated in workshops on kumiki (Japanese joinery techniques), gaining firsthand insights into the deep craftsmanship that wood embodies.

Nobuyasu: Wood has always been a part of our daily lives, and many people feel a natural connection to it — often without even realizing it. Since we’ve been surrounded by wood from a young age, we tend to develop an instinctive sense of comfort and preference for it.

What’s interesting is that while wood in nature can be rough and wild, it becomes warm and familiar once it’s shaped by human hands. That transformation — from something raw to something that fits beautifully into our homes — reflects the kind of harmony with nature that we truly care about.

From Philosophy to Design Principles — and Ultimately, to Interaction Guidelines

How is the philosophy of Calm Technology concretely applied to the mui Board?

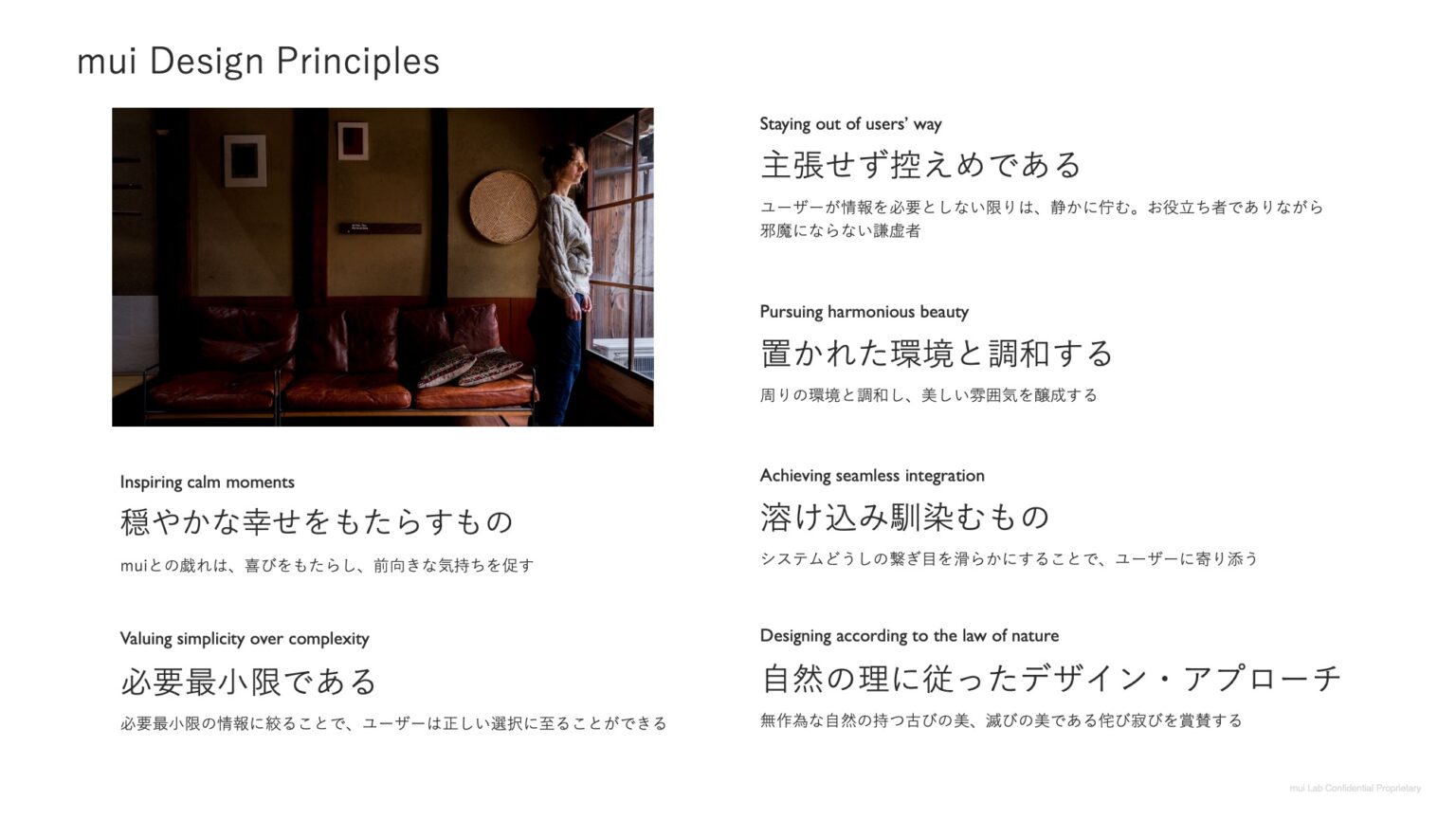

Eri: At mui Lab, we’ve developed our own six “Design Principles,” based on the foundational ideas of Calm Technology.

Nobuyasu: Let me share an example of how we’ve incorporated these design principles into our product.

Nobuyasu: In this photo, the woman is gazing out the window on a cold winter day, just as the snow begins to fall gently outside. What matters in this moment isn’t the mui Board as a digital device sitting in the room — it’s that she’s quietly taking in the scene beyond the glass. The mui Board’s weather display isn’t meant to steal her focus, but rather to subtly complement what she’s already sensing from the world around her.

We see the mui Board as an expression of our design principles: to remain modest, and to harmonize with its surroundings. It’s there to support the atmosphere of the space — not to dominate it, but to gently be part of it.

Eri: We brought these ideas to life in the mui Board, but applying them to other interfaces and experiences proved challenging. To make the principles more actionable, our design team held workshops and developed what we now call mui’s Interaction Guidelines.

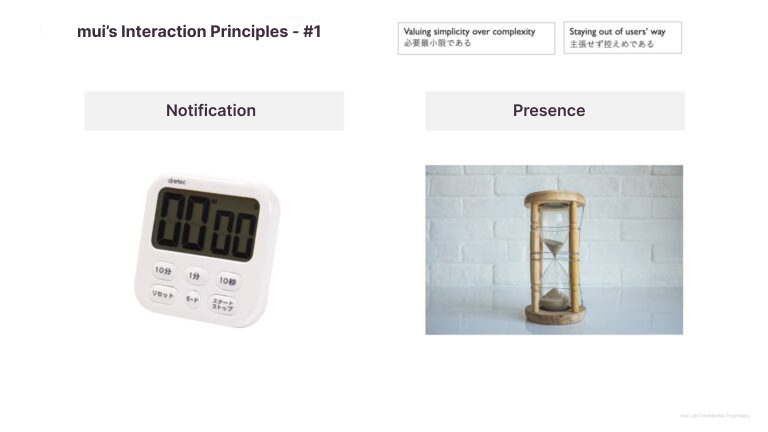

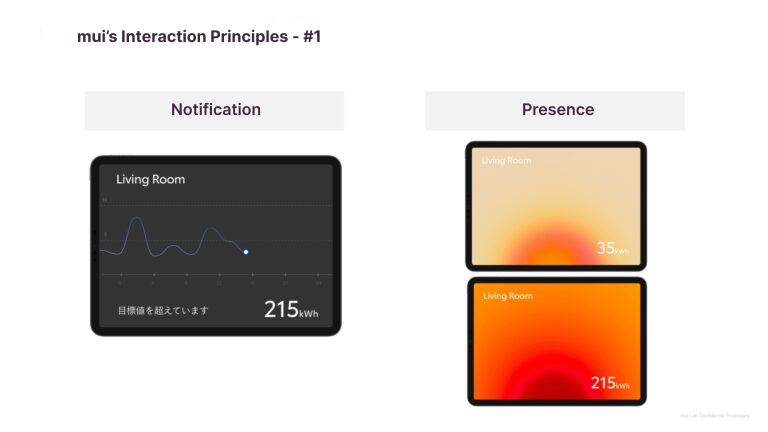

One key concept that emerged from this process is the relationship between “notification” and “presence.”

Eri: For example, a “notification” conveys information explicitly, like a digital timer that shows numbers and sounds an alert when time is up. In contrast, “presence” is more subtle, like a sand timer that quietly signals time has passed as the sand disappears. Notifications are passive—you notice them even without paying attention—and they depend on central vision because you have to look directly at them. Presence is active; it requires awareness and can be sensed through peripheral vision, like noticing the sand is gone without staring directly at it.

- Central vision: The area within approximately 30 degrees of your direct line of sight when you fix your gaze on a single point without moving your eyes.

- Peripheral vision: The area outside central vision, within the 180-degree field of view, where things are vaguely visible toward the sides.

How can these concepts be applied to a real interface? Take daily electricity usage as an example. A “notification” approach might show a graph with text clearly stating that the target has been exceeded. In contrast, a “presence” approach could use shifts in color intensity—such as a gradually deepening red—to subtly indicate overuse without drawing direct attention.

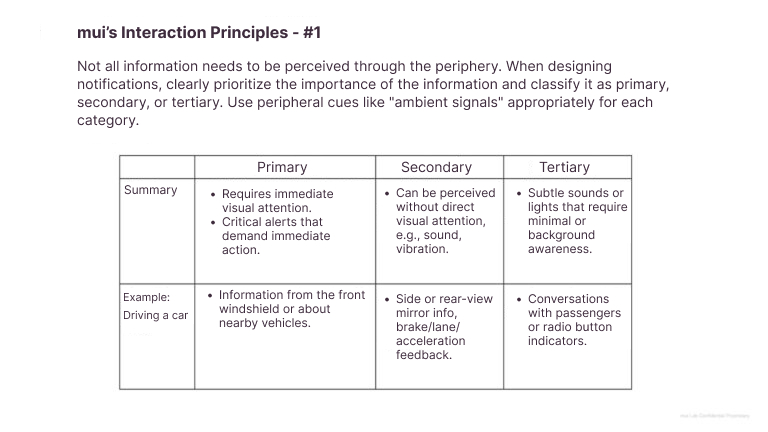

Eri: In addition, we also took into account the prioritization of notifications as defined in the book, Calm Technology: Designing for a Life in the Background, and decided not to deliver all information through peripheral cues alone. Instead, we classified information into three levels — primary, secondary, and tertiary — and designed lower-priority information in a more “presence”-based, ambient way.

Our goal is to identify what information truly matters and find ways to present it that invite awareness rather than demand it. In doing so, we hope to spark users’ memory and physical intuition, encouraging a more mindful and natural interaction with technology.

Based on your work with the mui Board, you’ve translated abstract ideas into more concrete design guidelines, haven’t you?

Eri: That’s right. By revisiting the mui Board and other products we’ve created, we’ve clarified what gives them a “mui Lab” identity. Putting those qualities into words helps us apply our distinct approach more consistently across various interfaces and experiences.

A Digital Product That Speaks Softly Like Furniture

As you mentioned earlier, now may be the right moment to rethink how digital products present information, especially in an age overwhelmed by an ever-growing volume of data.

Nobuyasu: Digital products often feel noisy. They constantly send notifications and try to explain themselves through their interfaces. But I think it’s perfectly fine for a product to reveal its purpose gradually, through use.

Take a kendama, a traditional Japanese toy. At first glance, most people wouldn’t know how to use it as there are no instructions printed on it. But by watching someone play or trying it firsthand, they begin to understand how it works and eventually enjoy it.

In contrast, digital products often come with QR codes and on-screen explanations, offering guidance right from the start. It’s as if we’ve all agreed that “understanding what something is in an instant” is correct — creating experiences that are defined by rules set by someone else.

It sounds like we’ve boxed ourselves into a singular notion of what a digital product should be. What kind of digital product is mui Lab aiming to create?

Nobuyasu: We see digital products and furniture as equals, or at least as deserving of equal consideration. A chair, for instance, is made for sitting, but people also use it as a step stool or a place to rest their belongings. Its function is simple, yet it allows for a variety of uses. I believe digital products could follow that model — simple, intuitive, and open to flexible interpretation.

If we move toward a future where “the home is connected via a network” becomes the norm, then even something as ordinary as sitting on a chair could be recorded in the cloud — enabling the home to recognize, “Someone is sitting here.” Without the need for cameras, the house could understand what’s happening through a combination of contextual signals. I imagine a home where everyday objects act as gentle sensors, quietly observing the environment and its residents, gradually deepening the home’s awareness.The mui Board was designed as an early step toward that vision — a way for us to begin understanding and visualizing what’s happening inside the home.

What does that vision look like in the mui Board’s technology?

Nobuyasu: While incorporating a range of technologies, we place great importance on “slow movement” in areas where people physically engage with the device. For example, when you touch the board to operate it, the touch sensor detects your input with high precision. However, transitions on the display are intentionally slowed down, so that you can’t operate it hastily.

That design choice reflects our intent: we want people to interact with the mui Board in a way that’s intentional and calm — similar to the comforting feeling of running your hand along a wooden stair rail. We hope users will feel a subtle sense of delight, like “just touching it feels nice, and maybe today will go well.” It’s almost like a charm. And fundamentally, we believe it matters that there’s a layer of wood between the user and the information.

Why Is the Feel of Wood So Important?

Nobuyasu: Because we think of the mui Board as furniture. We believe digital products, too, can become long-lasting parts of the home — just like furniture that holds memories: when it was bought, who used it, and so on. While the data itself lives in the cloud, we want it to feel as if the wood is quietly absorbing and preserving the memories of the home. That sense of warmth and continuity is at the heart of our design.

Besides using wood as a material, how else can design help bring that vision to life?

Nobuyasu: One thing we’ve done is make it possible to draw or write messages by hand, turning the mui Board into something people can use in everyday life. This allows users to leave messages like “Heat up your dinner and enjoy!” — just as you might leave a note on the dining table.

Those messages are saved in the mui Board‘s cloud and can be retrieved and displayed later. When something is written on paper, people often take a photo with their smartphone to preserve it. But then, to revisit that memory, you have to go through a digital screen. What if, instead, the content of a past message could softly reappear on a piece of furniture or a wall — like a memory floating to the surface?

Right now, messages appear only on the mui Board itself. But we imagine a future where different pieces of furniture are connected through a network, allowing thoughts and memories to gently resurface throughout the home. It could create a living space where emotional traces quietly emerge, adding warmth and depth to the atmosphere.

A New Vision for Smart Homes and Smart Cities — Toward a Future Where Technology Blends Naturally into Life

Finally, what direction do you see mui Board and mui Lab taking from here?

Nobuyasu: In the near future, the physical form of homes may stay much the same, but with the rapid evolution of generative AI, the digitization and smart integration of living spaces will only accelerate. As AI becomes a natural part of the home environment, it will reshape how we design user experiences and interfaces. We envision technology that feels more like furniture, soft, subtle, and open to interpretation, blending effortlessly into daily life.

So far, technology in the home has often fallen short of offering experiences that truly align with how we live. But by combining the tactile and emotional sensitivity that mui Lab values with IoT, and enabling AI to understand daily life while respecting privacy, we believe a new kind of smart home can take shape.

As these experiences accumulate, they’ll generate meaningful data, and that data could begin to influence how smart cities are designed and operate. Seen from a broader perspective, this future might even resemble something organic, like a living organism.

That’s the kind of digital technology design we’re aiming for at mui Lab — one that brings together natural materials and advanced tech, that taps into human senses and emotions, and that allows space for slowness, spontaneity, and play. These subtle, open-ended qualities are, we believe, the timeless foundation of meaningful design in an ever-changing world.

Special Thanks to:

mui Lab Inc. https://muilab.com/ja/

mui Board: https://muilab.com/ja/products_and_services/muiboard/